They

are the freelancers of terrorism: young men -- and some women -- who

feel alienated from the Western societies in which they live, hold

extremist religious views and embrace violence. They become immersed in

social media, searching out opinions that echo their own.

Now

they can find such opinions with one click and interact with jihadis in

combat thousands of miles away. On Twitter, Facebook and other social

media, they are encouraged or prodded toward joining the cause with

their own act of jihad.

The vast

majority will eschew that final step. Elton Simpson and Nadir Soofi in

Garland, Texas, did not. They are the latest examples of a growing

phenomenon that al Qaeda affiliates, and especially the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria,

or ISIS, have encouraged through prolific use of social media and more

traditional forms of "outreach" such as video and audio messages:

"do-it-yourself" acts of terror.

Texas gunman linked himself to ISIS in tweets

This stream of messaging feeds online radicalization, which "results from individuals being immersed in extremist content

for extended periods of time, the amplified effects of graphic images

and video, and the resulting emotional desensitization," in the words of

one report.

Like-minded

people can find each other very easily online and validate each other's

views. As psychologist Elizabeth Englander put it, "With the Internet, they can always find others who share their views. Suddenly there is a community that says, 'You're not crazy, you're right.' That's very powerful."

Terror

groups do not order or direct the do-it-yourself acts, nor even have

advance knowledge of them. Rather, their supporters keep up a constant

drumbeat of incitement via social media. They harp on acts they deem

hostile to Islam: cartoons of the Prophet Mohammed, coalition airstrikes

in Iraq and Syria, the burning of the Quran.

Taking the bait

In

one or two cases, the seeds they sow will germinate. In a video he shot

days before his attack on a Jewish store in Paris last January, Amedy

Coulibaly asked of fellow Muslims: "What are you doing my brothers? What

are you doing when they continually insult the Prophet?"

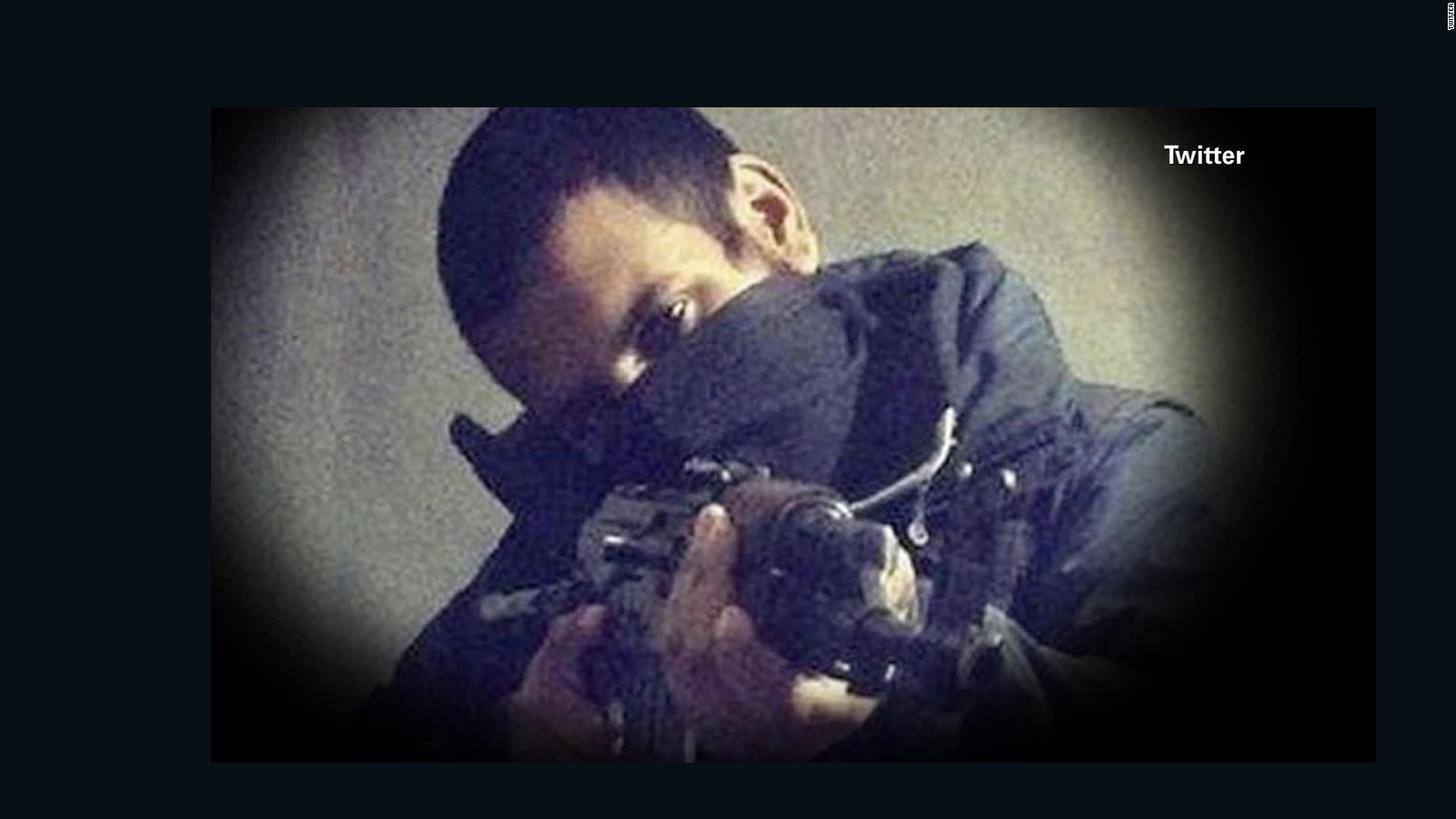

Simpson followed more than 400 users, "ranging from pro-IS supporters to hardcore IS fighters

from around the world," said Rita Katz, executive director of the

jihadist monitoring outfit SITE. And "many of them were also following

him."

Who is jihadi hacker Junaid Hussain?

The

costs to ISIS are minimal: no training, no funding, no risk that

leaders or other operations will be compromised -- just a constant

stream of invective. It's an old distinction -- inspirational against

operational, but taken to a new level. The reward for the terror group

is that some individuals may pledge allegiance to the self-styled

caliph, Abu Bakr al Baghdadi, before they commit a terrorist act, and

that enhances the perception of the group's reach. Simpson did so just

before the Texas attack; so did Coulibaly.

Some

ISIS members and followers, such as Junaid Hussain, who tweeted about

the attack on the Texas exhibition, might best be described as virtual

cheerleaders. They sit in Raqqa or Mosul with a laptop and an Internet

connection, ceaselessly tweeting about perceived injustices and insults

toward Islam, goading their followers.

It was another of these cheerleaders, Mujahid Miski, an American citizen now with Al-Shabaab in Somalia,

who praised Coulibaly and the Kouachi brothers (who carried out the

attack on the Charlie Hebdo office in Paris) in a tweet on April 23. He

also referred to the upcoming exhibition in Texas. "If only we had men

like these brothers in the #States, our beloved Muhammad would not have

been drawn," he lamented.

Elton Simpson, a Miski follower, retweeted the tweet. Perhaps it was then that he decided to act.

"I

believe that perhaps he might have just snapped when he heard about the

cartoon contest," said Kristina Sitton, an attorney who defended

Simpson in 2011 when he was convicted of lying to FBI agents about

wanting to travel to Somalia. There appear to have been direct messages

between Simpson and Miski after April 23, but their content is unknown,

Katz said.

Cheerleaders like Hussain

are not ISIS or Al-Shabaab leaders but tech-savvy foot soldiers often

barely out of their teens. Hussain was convicted in the UK for hacking

into former British Prime Minister Tony Blair's

personal address book and allegedly had a role in "outing" the personal

details of U.S. military personnel. He was formerly known as "TriCk" of

the hacking group TeaMp0isoN.

Avoiding authorities

It's

very difficult for counterterrorism agencies to guess who might be

influenced by such incitement. It's also difficult just to keep track of

so much social media activity, especially when someone frequently

changes handles or user names. Between mid-April and May 3, 2015,

Simpson changed his handle and username at least three times, Katz said.

And the language used is frequently obscure or abbreviated.

In

many societies where free speech is constitutionally protected, it's

often tough to prosecute someone calling for violence or "resistance" in

a foreign country, because authorities have to show that someone else

acted upon such a call. However, from France to Australia, laws are

being beefed up to make incitement in itself a crime, regardless of the

consequences.

There is no shortage of

such incitement. A groundbreaking study by the Brookings Institution

published in March estimated that in the last four months of 2014, ISIS

supporters used at least 46,000 Twitter accounts. They were active and

had an average of about 1,000 followers. Some are indeed hyperactive,

such as those of Hussain and Miski, whose real name is Mohammed

Abdulhali Hassan.

In a detailed analysis of social media profiles among foreign fighters with jihadist groups in Syria

and Iraq, the International Center for the Study of Radicalization

concluded that to them, "social media is no longer virtual: it has

become an essential facet of what happens on the ground."

Inside an ISIS recruit's path to extremism

Most

of these jihadist cheerleaders derive credibility from being in a

conflict zone, such as Syria or Somalia, providing news from the

battlefield in real time, often with videos and photographs. But being

there is not a prerequisite. ISIS supporter @shamiwitness, who sent some

128,000 tweets in English, turned out to be a 24-year-old information

technology worker in Bangalore, India. He had 17,000 followers when he

was exposed and arrested in December of last year. As Hassan Hassan put

it in Foreign Policy, @shamiwitness served in many ways as a " 'virtual inn,' where jihadist travelers linked up."

Another

remote supporter of jihad is Australi Witness, who had, like Miski,

highlighted the Texas event in advance, and commended the attack on it.

He was careful to distance himself from involvement, telling the Sydney

Morning Herald: "I support what our mujahideen in Texas did, but I take

no responsibility for it. Allah commanded them to attack, not me."

His Twitter account has been suspended, but he is thought to have re-emerged, posting a guide on how to get to Syria and Iraq

to wage jihad. And he is quoted as telling the Herald: "This is a war

that will be won through the power of social media. We are winning the

minds of the young generation."

The

International Center for the Study of Radicalization analysis found that

such "disseminators" have been highly influential among foreign

fighters in Syria and Iraq. @shamiwitness was followed by two-thirds of

the foreign fighters analyzed in the center's report, giving him

credibility among would-be jihadists far from the field of combat.

But

for the jihadist groups, these disseminators are a double-edged sword,

answerable to no one. They may have views the hierarchy opposes. They

could be banished from old-fashioned chat rooms, but that's "no longer

possible on Twitter where both fighters and their supporters are able to

engage in wholly unregulated conversations about whatever they please,"

according to the center.

Appealing to the spirit

Some

Muslim extremists in the West may also turn to a new generation of

"spiritual guides" -- the successors of American-born cleric Anwar al-Awlaki, whose image was the avatar on Elton Simpson's Twitter account.

Agent Storm: Anwar al-Awlaki had charisma

For

years, when in the UK and later in Yemen, al-Awlaki was careful not to

incite for violence in Western countries nor directly encourage young

men to travel for jihad, even as he justified it as legitimate

resistance.

Gradually, his views hardened, especially after a stint in a

Yemeni jail. His lectures justifying acts of violence in the West have

been highly influential -- on Fort Hood shooter Nidal Hassan and the Boston bombers, among many others.

Australian-born

preacher Musa Cerantonio may have none of al-Awlaki's learned guile,

and much of his social media output is devoted to supporting jihad in

Syria and Iraq. But his language may also feed the animosity of his

audience toward Western governments. At the end of 2013, he posted on

Facebook: "If we see that Muslims are being killed by the tyrant leaders

of the USA then we must first stop them with our hands [ie by force].

This means that we should stop them by fighting them, by assassinating

their oppressive leaders, by weakening their offensive capabilities

etc."

Cerantonio was deported from the Philippines to Australia last year and has been careful to tone down his public utterances in interviews with Australian media since returning home in an effort to avoid prosecution.

But

the International Center for the Study of Radicalization argues that

"whether consciously or not, (spiritual figures) may be performing an

important role in the radicalization of some individuals and retain this

importance among those who later decide to engage in active combat."

Again, for authorities, making the link between cause and effect in a

court of law is an immense challenge.

Twitter

has become more aggressive in identifying and closing ISIS-related

accounts, but as Junaid Hussain has repeatedly shown, it's a game of

cat-and-mouse. And followers quickly inform each other of a new account

handle. Miski is known to retweet Hussain's messages -- and was on his

31st account when he made his call for violence in Garland, says Rita

Katz at SITE.

Katz argues that such

accounts, when they can be identified, must be terminated, writing that

"Leaving accounts like Miski's active on social media for the sake of

acquiring intel is like leaving landmines in a public field to study

their placement."

Others argue that attempts at censorship are both undesirable and futile. In its report "Countering Online Radicalization in America,"

the Bipartisan Policy Center said it would be more fruitful to exploit

"online communications to gain intelligence and gather evidence" while

also tackling the demand for violent extremist messages through

education.

That debate will no doubt

continue, as the dynamics between terror groups and their far-flung

acolytes also evolve, and counter-terrorism agencies scramble to

distinguish intent from bluster among the trillions of social media

messages.

Culled from:

No comments:

Post a Comment